Defence acquisition is entering a period of profound transition. For decades, the prime contracting model has been the backbone of procurement in the UK, US, and across Europe. It has delivered capital intensive platforms — aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines, fifth generation fighters — but at the cost of speed, flexibility, and inclusivity. In contested domains where adversaries iterate technologies in weeks, not years, this model is increasingly misaligned with operational realities [1][3][21].

The war in Ukraine has underscored the urgency. Low cost drones, loitering munitions, and commercial satellite constellations have reshaped the battlespace faster than traditional acquisition cycles can respond [10][11]. Governments are beginning to adapt, but cautiously. The challenge is not to dismantle primes, but to rebalance the ecosystem: integrating their strengths with the agility of SMEs, dual use firms, and modular technologies.

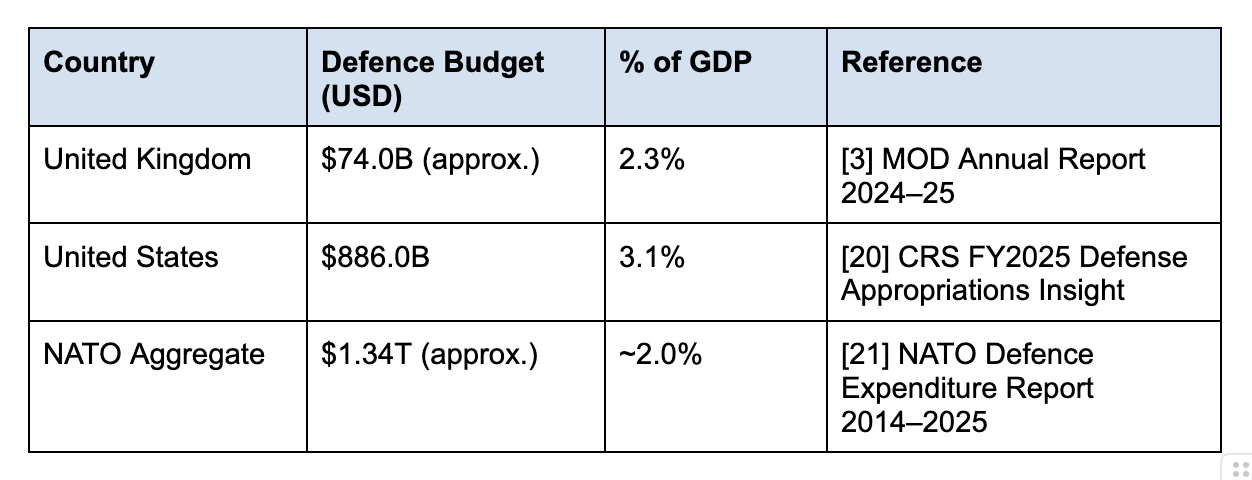

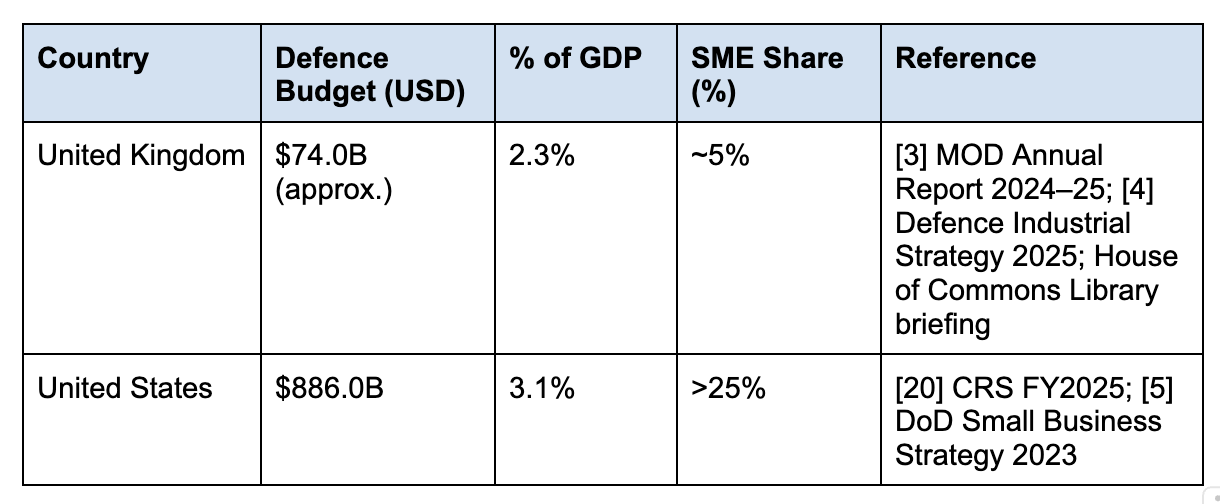

Comparative Defence Spending – UK, US, and NATO

Limits of the Prime Contracting Model

Prime contractors have historically provided sovereign assurance, scale, and integration. Programmes such as the F35 Joint Strike Fighter, the Columbia class submarine, and the UK’s Type 26 frigate exemplify the model: multi decade, multi-billion dollar undertakings requiring deep industrial capacity. Yet these programmes also highlight systemic weaknesses:

- F35 programme: lifecycle costs exceed $1.7 trillion, with persistent delays in software integration [6].

- Columbia class submarine: projected to cost over $110 billion, with delivery timelines stretching into the 2040s [7].

- Type 26 frigate: delays and escalating costs raise questions about whether traditional contracting can deliver naval capability at required pace [3].

Beyond cost and schedule, the model is structurally risk averse. Gatekeeping processes often exclude SMEs and dual use firms, limiting access to disruptive technologies. Traditional acquisition cycles struggle to incorporate rapidly evolving domains such as AI, autonomy, and edge computing [4][5].

Emerging Government Responses

Governments are beginning to acknowledge the problem, though reforms remain incremental.

United Kingdom

The Strategic Defence Review 2025 calls for faster, more agile procurement. Initiatives such as Commercial X, the Neutral Vendor Framework for Innovation, and the newly announced Office for Small Business Growth are designed to engage SMEs directly and accelerate contracting [1][2][4].

Announced in November 2025 and due to launch by January 2026, the Office is a virtual MOD body created to support SMEs, start‑ups, and non‑traditional suppliers entering or scaling within the defence sector. It will simplify entry routes into the MOD supply chain, deliver SME policy objectives from the Defence Industrial Strategy 2025, and operate under the National Armaments Director Group as part of the wider “Backing Your Business” agenda. Developed through consultation with SMEs, primes, trade associations, regional clusters, and academia, it will provide a digitally enabled, user‑centric service to both industry and MOD teams.

This institutional development signals a serious intent to rebalance procurement and unlock SME‑led innovation, provided it is stood up with coherence, access, and clear routes to MOD spend.

United States

The US faces a similar dilemma. While mega primes dominate, initiatives such as the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), AFWERX [26], and the Commercial Solutions Opening process have enabled successes like the Blue UAS programme [25]. Yet the broader ecosystem remains tethered to primes, with programmes like Next Generation Air Dominance absorbing vast budgets and timelines.

Europe and NATO

Europe presents a mixed picture. The European Defence Fund [27] has begun to channel resources into collaborative projects among SMEs and primes, fostering modular innovation. NATO’s DIANA accelerator [24] supports dual‑use startups across member states, with a focus on AI, quantum, and autonomy.

Lessons from Ukraine

The war in Ukraine has provided a live case study in the limits of traditional acquisition. Systems such as the Turkish Bayraktar TB2 [10] and improvised commercial quadcopters have been iterated in weeks, not years.

Commercial satellite constellations like Starlink [11] have provided resilient communications under fire, bypassing traditional procurement entirely.

Ukrainian forces have integrated new technologies in theatre, creating feedback loops between frontline needs and innovation. This iterative approach contrasts sharply with Western acquisition cycles, which often take years to incorporate new capabilities [10][11].

The Drone Market Boom

The global drone market illustrates the scale of transformation. Valued at $73.06 billion in 2024 it is projected to more than double to $163.60 billion by 2030 (Grand View Research). Growth is driven by advances in autonomous systems, AI powered sensors, and multi-domain applications spanning defence, aerospace, logistics, and public safety [12][13][14].

While primes and corporates play a role, the real energy lies with startups and early stage OEMs. Their success depends on access to capital, strategic alliances, and a clear path to market. Venture capital firms such as Andreessen Horowitz, Lux Capital, and Eclipse Ventures have backed companies like Zipline [15] and Skydio [16]. Government programmes provide critical early stage support: Innovate UK’s Future Flight Challenge [12], the European Innovation Council Fund [13], the UK Defence and Security Accelerator [14], and US initiatives such as DIU [25], AFWERX [26], and Other Transactional Authority pathways. NATO’s DIANA [24] programme has also emerged as a launchpad for multiphase awards and partnerships.

Towards a Hybrid Model

The future is not about replacing primes but rebalancing the ecosystem. Primes should act as integrators rather than gatekeepers, leveraging their capacity for sovereign assurance and complex systems integration. Vendor neutral platforms can scale disruptive technologies without lock in, while open architectures enable interoperability and reduce dependency on single suppliers [24][27].

In software defined domains, capability-as-a-service offers a shift from ownership to mission delivery. In theatre innovation loops can feed real world feedback directly into procurement cycles [25][26].

Case Studies in Hybrid Approaches

Several programmes already illustrate elements of this hybrid model. The Royal Navy’s NavyX innovation cell is testing autonomous vessels and modular payloads in

Royal Navy – NavyX Innovation Cell

The Royal Navy’s NavyX innovation cell is testing autonomous vessels and modular payloads in live environments, providing a pathway for faster experimentation and integration [8].

US Army – Project Convergence

The US Army’s Project Convergence experiments with AI‑enabled decision‑making and integrates commercial technologies into operational exercises, demonstrating how agile innovation can be embedded into joint operations [9].

NATO and European Defence Fund

NATO’s DIANA accelerator supports dual‑use startups across member states, while the European Defence Fund [27] is funding collaborative projects among SMEs and primes. Together, these initiatives foster modular innovation and cross‑border collaboration.

ePropelled – Sovereign Supply Chain Pivot

A standout example of agile subsystem innovation is ePropelled, a next‑generation propulsion company powering the future of defence and autonomous mobility. When China imposed sweeping rare earth export restrictions in 2025, ePropelled anticipated the strategic risk and pivoted early. It developed a sovereign manufacturing approach, securing domestic supply chains and becoming one of the first companies to partner with US Rare Earths [23]. This move pre‑empted the global magnet shortage — a critical component in electric propulsion — and reinforced the company’s role as a resilient subsystem provider [22][23].

SME's as Strategic Advantage

Such firms demonstrate how SMEs can deliver strategic advantage through foresight, agility, and sovereign alignment, especially when primes act as enablers rather than gatekeepers. Beyond subsystem innovation, SMEs deliver measurable strategic value. In the UK, 60% of defence SMEs export directly to NATO allies, while 25% supply Ukraine — embedding sovereign industry into alliance resilience. In the US, small businesses secure over 25% of DoD contracts, leading advances in AI, autonomy, and cyber. Programmes like AFWERX and DIU demonstrate how SMEs shorten innovation loops, feeding operational feedback directly into procurement. NATO’s Emerging and Disruptive Technologies Strategy further underscores SMEs as accelerators of alliance agility. These contributions show SMEs are not marginal suppliers but strategic assets: agile, sovereign‑aligned, and alliance‑integrated.

Israel – Commercial Drone Integration

Israel’s integration of commercial drone technologies into military operations has shown how SMEs can deliver battlefield advantage at speed.

United States – Zipline & Skydio

In the US, Zipline’s [15] autonomous delivery drones, initially developed for medical logistics, are now being evaluated for defence applications. Skydio’s [16] AI‑enabled quadcopters have transitioned from commercial inspection to tactical reconnaissance, highlighting how commercial innovation can rapidly migrate into defence use cases.

NextGeneration Primes: Disruptors or New Gatekeepers?

Companies such as Anduril Industries [17] and Palantir Technologies [18] are often described as “next generation primes.” They are agile, software driven, and celebrated for breaking conventions in the defence ecosystem. Anduril’s autonomous systems and Palantir’s data fusion platforms have won billion dollar contracts, including joint awards under the Pentagon’s Replicator programme [19].

Yet despite their disruptive ethos, they risk replicating the traditional prime formula: commanding the lion’s share of budgets and acting as gatekeepers to SMEs. The question is whether procurement can be flipped — allowing SMEs to bid as lead contractors, backed by heavyweights for integration and compliance. Such a model would empower SMEs, diversify risk, and accelerate innovation, while still ensuring sovereign assurance.

The Strategic Imperative

Adversaries are not waiting. China’s military civil fusion strategy integrates commercial innovation directly into defence, ensuring that advances in AI, quantum computing, and autonomy flow seamlessly into military capability [22]. Russia’s adaptation in Ukraine shows how lowcost technologies can offset industrial disadvantages [10][11].

For Western nations, the imperative is clear: resilience through diversified suppliers, speed through modular technologies, and sovereignty through engagement with domestic SMEs. Failure to adapt risks strategic imbalance. Success requires rethinking procurement not as a bureaucratic process, but as a competitive advantage [21][24][27].

Conclusion

The prime contracting model has delivered scale and assurance, but at the cost of agility. In contested domains, that tradeoff is no longer sustainable. Governments are beginning to respond, but cautiously. The future lies in hybrid models that integrate primes with SMEs, dual use firms, and modular technologies.

This is not disruption for its own sake. It is disruption for survival. Defence acquisition must evolve — modular, open, faster, in theatre, under pressure, at speed. The choice is stark: disrupt or be disrupted [1][3][24][27].

.png)

.jpg)